Making Sense of Mahmoud v. Taylor

The Supreme Court's ruling likely won’t end classroom content controversies—because defining “curriculum” isn’t as clear-cut as SCOTUS seems to assume.

The Supreme Court’s decision last week in Mahmoud v. Taylor was cheered by conservatives and religious liberty advocates. The 6-3 ruling found that a Maryland public school district violated the First Amendment’s Free Exercise Clause by refusing to let parents opt their elementary school children out of lessons featuring LGBTQ-themed storybooks. The Court reaffirmed a bedrock principle going back a century to Pierce v. Society of Sisters: Parents cannot be forced to have their children exposed to material that conflicts with their religious beliefs, certainly not without notice and the opportunity to opt out.

But don’t be surprised if Mahmoud proves to be less than the last word. Not because SCOTUS’s legal reasoning is muddled—it’s not—but because of the way reading is taught in many elementary classrooms. The gap between how courts think “curriculum” works and how it’s actually implemented in elementary classrooms is vast. And that means schools will likely keep finding themselves on the receiving end of angry phone calls, and possibly lawsuits, from parents blindsided by what their children bring home in their backpacks.

In Mahmoud, the books in question weren’t part of the Montgomery County school district’s core curriculum. A few years ago, the MCPS school board “determined that the books used in its existing [English language arts] curriculum were not representative of many students and families in Montgomery County because they did not include LGBTQ characters,” according to the majority opinion written by Justice Alito. The board decided to introduce “LGBTQ+-inclusive texts.” Five books for younger students were at issue in Mahmoud: Intersection Allies, Prince & Knight, Love, Violet, Born Ready: The True Story of a Boy Named Penelope, and Uncle Bobby’s Wedding.

As described in the majority decision, the school board suggested “that teachers incorporate the new texts into the curriculum in the same way that other books are used, namely, to put them on a shelf for students to find on their own; to recommend a book to a student who would enjoy it; to offer the books as an option for literature circles, book clubs, or paired reading groups; or to use them as a read aloud.” This is easily recognizable as the “reader’s workshop” model, which relies on students self-selecting books from a “classroom library” (not to be confused with a larger, stand-alone school library) – bins filled with dozens of books, even hundreds of them, on shelves in a child’s classroom, sorted by reading levels, genres, or themes, and providing time for both independent and guided practice. In the workshop model, teachers lead “mini-lessons” on a reading “skill” or “strategy” from a common text. But students typically practice on books they choose themselves—on the theory that this generates kids’ interest and engagement.

The workshop model also relies heavily on whole-class read-alouds, which is the principal source of the conflict in Mahmoud. The Court looked askance, for example, at a 2022 professional development session that advised teachers to correct students who make “hurtful comments” on transgender issues. “When we’re born, people make a guess about our gender and label us ‘boy’ or ‘girl’ based on our body parts,” they were advised by the district to explain. “Sometimes they’re right and sometimes they’re wrong.” A guidance document also encouraged teachers to “disrupt the either/or thinking” of their students about biological sex. Initially, MCPS allowed parents to opt out of read-alouds featuring the controversial books, but later rescinded that option. It was this shift—the loss of notice and opt-out rights—that the Court found constitutionally unsupportable: Parents were denied the opportunity to withhold consent on religious grounds.

What counts as “instruction?”

“The books are unmistakably normative,” SCOTUS ruled. “They are designed to present certain values and beliefs as things to be celebrated, and certain contrary values and beliefs as things to be rejected.” Neither did the Justices accept Montgomery County’s argument that its “LGBTQ+-inclusive” instruction was mere “exposure to objectionable ideas” or as lessons in “mutual respect.” The storybooks “unmistakably convey a particular viewpoint about same-sex marriage and gender. And the Board has specifically encouraged teachers to reinforce this viewpoint and to reprimand any children who disagree. That goes beyond mere ‘exposure.’”

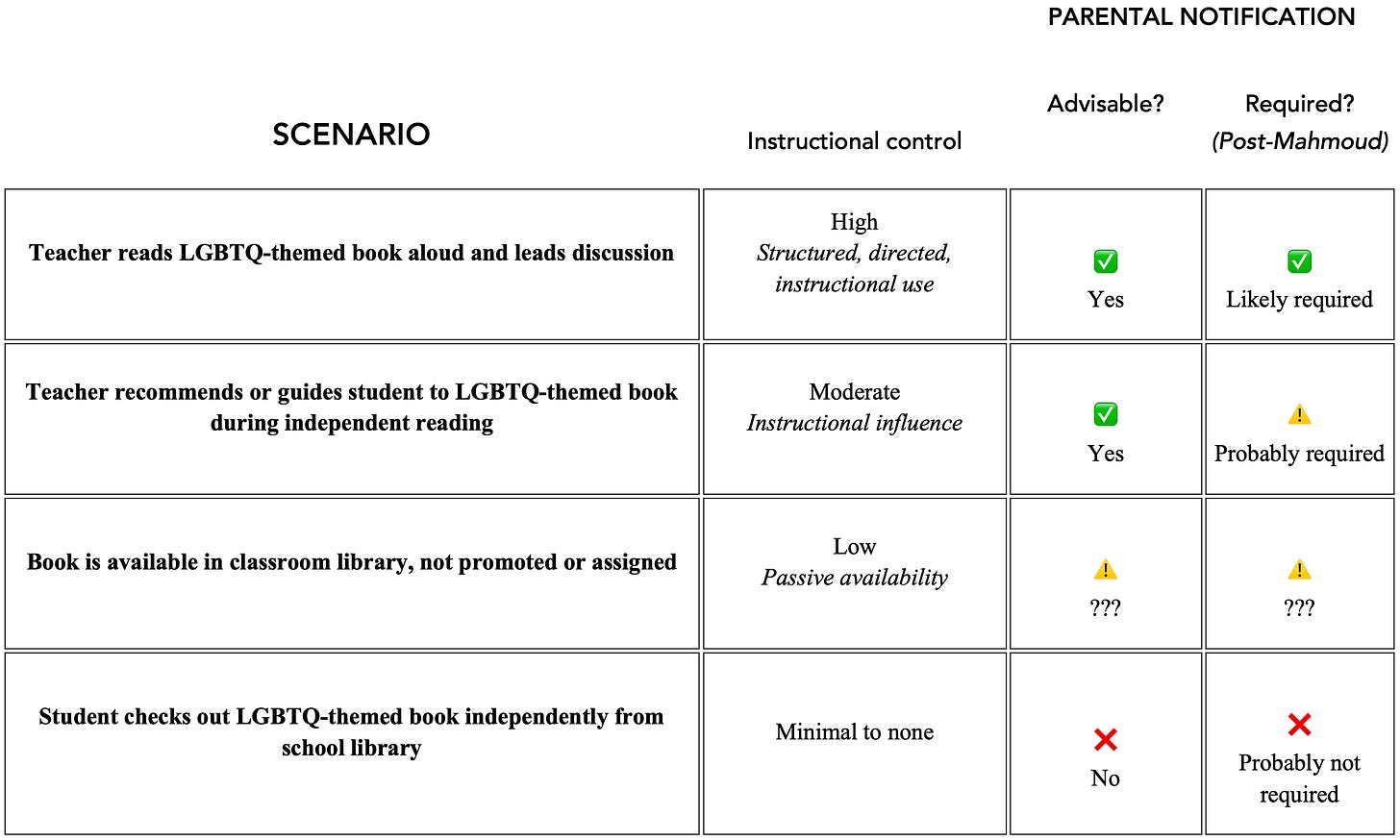

The line the Court drew seems bright: If schools use contested materials instructionally—especially in ways that make exposure unavoidable—parents have a right to know and a right to say no. Montgomery County’s approach and guidance seems heavy-handed and didactic. But in common practice, the line between “instructional” and “not instructional” is far from clear. Many elementary classrooms today don’t assign novels or shared texts; the teacher teaches literacy skills, not books. A question surely on the minds of teachers, administrators, and school board members who’ve read the decision is one the Court left unaddressed and may not even be aware of: is the line crossed only when controversial books are read aloud? Or is their mere presence in a classroom library enough to require parental notification, since students might choose them as part of their ELA instruction? No consideration in either the majority decision or the dissent authored by Justice Sotomayor seems to have been given to the difference between a classroom library or a school’s main library, or (apart from a whole-class read aloud) how a controversial book might end up in a child’s hands.

From a judicial perspective, it might matter whether a book is “assigned” and exposure compelled. But from a parent’s perspective, it probably doesn’t. If a first grader comes home with It’s Okay to Be Different or I Am Jazz, parents are unlikely to distinguish between something their child picked up on her own and something their teacher handed them. Nor should we assume that the difference is meaningful. The classroom library didn’t build itself. Teachers or other school district personnel chose what went on those shelves. And students made their selections during instructional time, under adult supervision, as part of a structured literacy program. In other words, “We didn’t assign it” may not be much of a defense.

Most non-educators—including parents, policymakers, and judges—think of “curriculum” as a list of books that every child reads. Something on the syllabus. A shared text. Yet that’s not how ELA works in many classrooms anymore. Although the workshop model has come under fire in recent years, it’s still a common, even dominant approach to elementary reading instruction across the country.

When a child chooses a book that contradicts the family’s religious or moral beliefs, it may not have been “assigned” per se but that doesn’t mean it’s neutral. It was placed there for a reason. And when it’s chosen during class time, under the implicit encouragement of an adult, it becomes part of the instructional environment. But does Mahmoud require parental notification of its simple existence in that environment? SCOTUS appears not to have weighed this possibility, which is far more likely than a controversial book being chosen for a whole-class read aloud.

This is where Mahmoud and classroom practice potentially—and predictably—collide. The Court treated the issue as one of compelled exposure. But in an ELA class built on student choice, what counts as “compelled”? If you make available a limited, curated set of books is that choice is free or coerced?

In the final analysis, there is a foreseeable mismatch between the expanded, ambient definition of curriculum inside schools and the traditional, content-focused definition held by the public. The Court didn’t resolve that mismatch. It barely acknowledged it and, indeed, might not be entirely cognizant of it. But it will almost certainly keep generating friction.

As a teacher, I would include books representing all ideas as choices in my classroom. (I taught adolescents, not young children.) I would also inform parents at the beginning of the year that I am making these texts available, and it is their job to have a conversation with their child about what is appropriate for their child to read and not, so their child will make choices in line with those values. If parents had an issue with that approach, they had to sign the paper and have their child return it so we could discuss how to handle it.

If this case were about the presence of the books in the classroom and parents wanting to remove choices for other people’s children, that seems problematic, but this case seems to focus on parents expressing rights for their child and not being allowed to do so.

As you suggest, what if a school has not informed parents and their child comes home with a book that doesn’t align with their values? In this scenario, I believe it puts the responsibility on the teacher. That teacher then ends up being the values police for all kids in the classroom, which I agree could lead to additional lawsuits. By informing parents and making it clear that they have both rights and responsibilities when it comes to the text selection their child makes, I think it helps to head off many potential issues.